They Said the Quiet Part Out Loud: Inside the latest MLC meeting that put city workers, retirees and their families' health data 'For Sale'

MLC leaders met on Friday the 13th. And it was as scary as billed.

“So… Are We Being Held Hostage?”

The question didn’t come from a script. It came from the tension in the virtual meeting room.

The informational meeting itself was convened because the City and its health care partners want the over 100 city union locals that comprise the Municipal Labor Committee (MLC) to share their welfare fund prescription drug data to support additional projected savings of the new NYC Employees PPO.

As revealed by leaked audio obtained by The Wire, the discussion quickly moved beyond technical questions into how participation shortfalls would be handled if unions refused.

After nearly an hour of discussion about projected savings, participation thresholds, prescription drug data, and repeated reassurances that everything being proposed was “normal,” a union leader finally asked what many people had been thinking:

“So… are we being held hostage?”

It wasn’t a provocation. It was an attempt to understand the leverage at play.

If unions don’t agree to share prescription drug data, what actually happens next? Does the issue simply go away? Or does it come back later—during contract talks, benefit negotiations, or arbitration?

The answer mattered. And the response that followed clarified the real pressure point.

MLC leadership explained that if the projected savings tied to the new health care plan are not achieved, the City carries that gap forward. It doesn’t disappear. It becomes part of the City’s argument in future labor negotiations—used to justify demands for benefit changes, cost shifting, or concessions in the next round of bargaining.

The discussion made clear that failing to meet the plan’s savings assumptions would not simply be absorbed by the City. As captured in the meeting audio, those gaps would be carried forward and used in future negotiations—and potentially pending arbitrations—as evidence that unions did not deliver on health care cost containment.

No one said unions would be punished for saying no. But everyone understood the implication.

That was the moment the meeting stopped being an information session and became something else entirely.

What That Question Changed

Up to that point, the discussion had been framed as technical and optional. Data sharing was described as voluntary. Participation targets were presented as goals. Savings were discussed as estimates.

Once it became clear that unmet savings would be banked and leveraged later, everything else had to be understood differently.

From that moment on, the meeting wasn’t really about whether prescription drug data should be shared. It was about whether unions realistically had the freedom to refuse—or whether saying no today simply meant paying a higher price tomorrow.

The $100 Million Hanging Over the Room

The discussion kept circling back to the same figure: roughly $100 million in projected savings tied to the NYC Employees PPO.

Leadership framed these savings as necessary to stabilize health care costs and preserve benefits. But what became clear is that the savings are not guaranteed. They depend on participation—specifically, whether enough unions agree to share prescription drug data.

Roughly 75 percent participation was cited repeatedly. Hit that number, and the plan works as designed. Miss it, and the savings gap doesn’t vanish—it becomes future leverage for the City.

This was not a neutral discussion about data governance. It was a conversation conducted under the shadow of upcoming contract negotiations.

When “Data Sharing” Became a Concrete Demand

As the meeting continued, unions began asking basic questions: how would the data be shared? Who would receive it? What additional costs will Welfare Funds bear in this data transfer? How often?

The answers were delivered calmly and antiseptically.

Prescription drug data would flow directly from union PBMs to the carrier. It would be sent weekly. This was described as standard practice.

But weekly prescription data is not routine. It is a detailed, constantly updated record of what medications people take, what conditions they are treated for, and how their care changes over time. It allows future costs to be anticipated and managed before they ever show up in claims.

Importantly, this data does not relate only to union members themselves. It includes their spouses, children, and other covered dependents, sweeping entire families into the same AI-driven analytic and scoring systems.

When the Real Value of the Data Slipped Out

At one point, almost in passing, an MLC leader referenced the prescription drug data itself as being worth around $500 million.

There was no valuation process behind that number. No bidding. No negotiation. The $100 million figure discussed throughout the meeting was not payment for the data—it was an estimate of how much money could be saved by using it.

That distinction matters.

It means unions are not being compensated for a valuable asset created by members’ and dependents’ lives, illnesses, treatment histories and other related personal information. They are being asked to give it up so the City and its insurer can strengthen their hand in future negotiations.

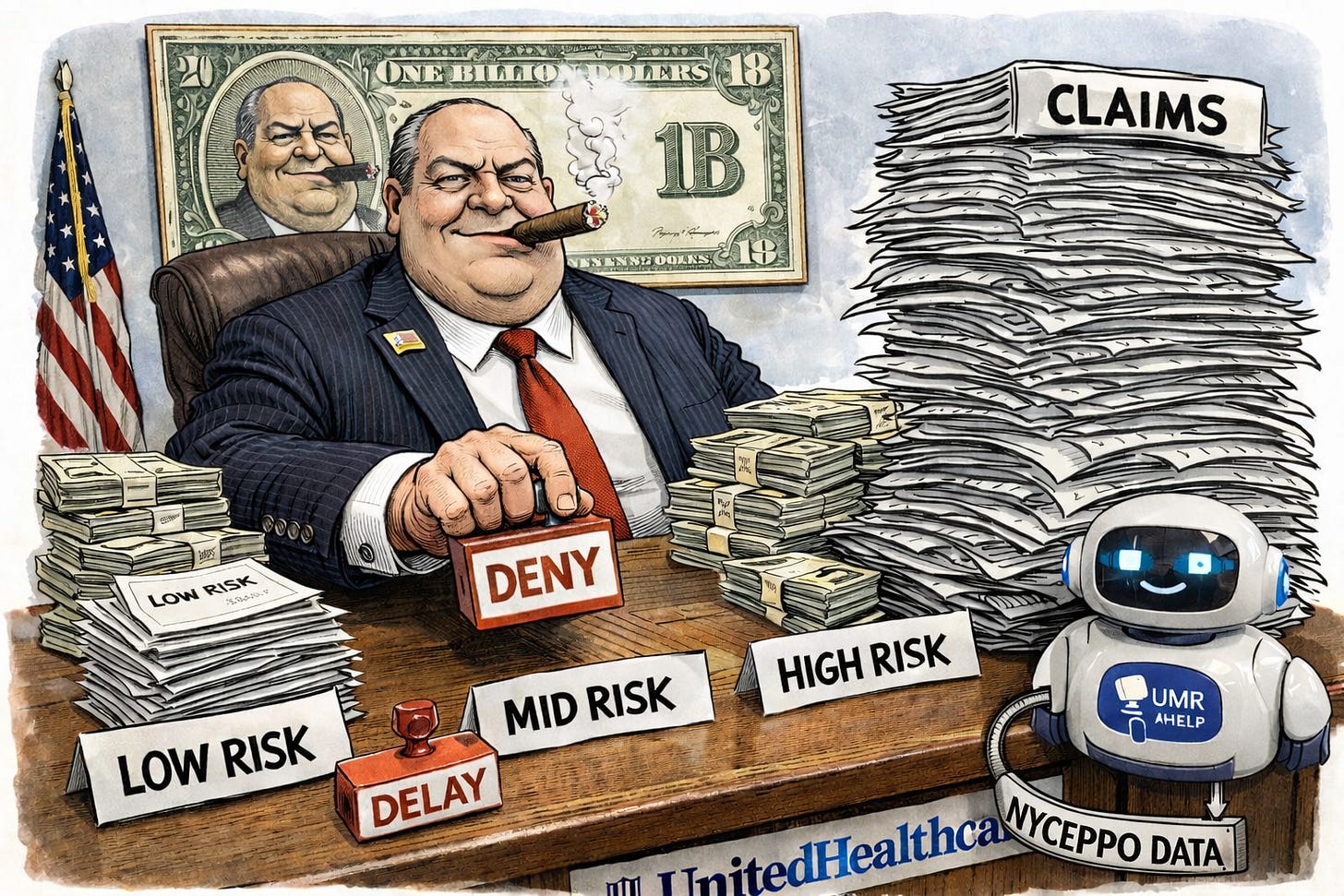

Tiered Risk Scores — What Really Happens When You’re Labeled “High Risk” by AI

When the meeting turned to risk scoring, the structure became clearer—and more troubling.

Members would be sorted into three tiers — low, mid, high — with each tier determining how closely their care would be monitored and managed. While presenters framed this as a way to “prioritize outreach,” the effect is obvious: the sickest, most vulnerable people are flagged first, watched most closely, and subjected to the most intervention.

In a system designed to generate savings, that intervention does not mean more generous care. It means more scrutiny.

By definition, tiered risk scoring concentrates attention on older members, people with chronic illnesses, disabled members, and those requiring ongoing medication or specialty care—the very populations most likely to generate higher costs.

What stood out was not what was said, but what wasn’t.

When Henry Garrido, President of DC 37, asked directly whether demographic factors such as age, gender, race, or ethnicity were incorporated into the risk models, the question went unanswered. Presenters fumbled and spoke generally about algorithms, while they avoided confirming what variables were actually used, how they were weighted, or how bias would be meaningfully mitigated.

They simply answered that they have a “nationally recognized” committee that ensures there’s no bias. The name of the committee was not shared, nor their methodology, nor who funds it.

That silence matters. Age alone can drive a risk score. Disability status and pre-existing conditions can too. And race and ethnicity often enter predictive models indirectly—through historical utilization patterns shaped by unequal access to care, systemic bias, and disparities in diagnosis and treatment.

When race, age, or disability function as proxies for cost risk, tiered scoring risks hard-coding existing inequities into benefit administration—raising serious questions about fairness and discrimination, even if no one says those words out loud.

In practice, tiered scoring does not sort members by who needs help. It sorts them by who is expected to cost money. Once a member lands in a higher tier, prior authorizations increase, step therapy becomes more common, and approvals take longer. This alone dispels the talking points that there’s no bias in this AI predictive model.

For elderly, disabled, chronically ill members—and communities already facing barriers to care—that friction is not incidental. It is inherent and structural.

Why “Care Management” Usually Means Denials and Delays

Throughout the meeting, leadership described the plan as “care management” designed to reduce redundancy and “holistically” help patients get healthier.

In a self-funded plan, redundancy means utilization. And reducing utilization is how savings are created.

Once prescription data and risk scores are in place, care doesn’t get coordinated so much as filtered. Tests require preauthorization. Medications trigger step therapy. Procedures slow down under review. Scores are inextricably tied to denials.

Friction is intentionally caused by United Healthcare’s subsidiary, United Medical Resources (UMR).

When we talk about friction, we are not talking about thoughtful oversight or better coordination. Friction is the accumulation of small obstacles that make care harder to get: extra paperwork, repeated phone calls, new forms, longer waits, and constant justifications for care that was once routine. For people who are sick, elderly, disabled, or already marginalized, friction is often the difference between timely care, life-saving procedures and worsening health.

“Financial Navigation” Is Cost Control by Another Name

When UHC presenters talked about “financial navigation,” they framed it as help.

In reality, it is about steering care based on price, not simply medical need.

It inserts the insurer into decisions that used to be between a patient and a doctor—questioning prescriptions, pushing substitutions, delaying needed treatments and procedures, and nudging members toward cheaper paths.

Called help, it functions as control over care — motivated by profits.

“We’re Only Here to Help”

Throughout the meeting, UHC and UMR presenters repeatedly cast themselves as neutral helpers.

But let’s be honest, UnitedHealthcare is not a benevolent, altruistic partner; it is the largest for-profit health insurer in the country, widely criticized for leading the industry in denials, delays, and aggressive utilization management. UMR applies that same model inside self-funded plans like New York City’s.

The data’s value comes from control.

“The Welfare Fund Owns the Data.” Does It?

Presenters reassured unions that welfare funds would “own” the data.

Ownership on paper is not control in practice. Once prescription-level data is transferred weekly, integrated into analytics, and used to train models, it cannot be meaningfully clawed back. The insights learned belong to the insurer and train its systems.

The Change Healthcare Breach — and Why It Matters

UnitedHealth Group’s tech subsidiary Change Healthcare suffered the largest health data breach in U.S. history, exposing over 192 million Americans.

This matters. The same corporate ecosystem now seeking weekly prescription-level data has already shown it cannot guarantee security at scale.

And this is the same United Healthcare that leads the industry in claim denials.

Once shared with UHC, data cannot be unshared.

A Seat at the Table — and a Position Already Taken

Legal counsel for the UFT Welfare Fund was present during the Friday discussion. As was UFT Welfare Fund Director, Geof Sorkin, who expressed enthusiastic support for moving forward with the data transfers saying it was just about “care management”.

That mattered. When one of the the largest and most influential unions signals acceptance early, it narrows deliberation for everyone else.

It also revealed context not disclosed to members or the MLC: the UFT Welfare Fund has used UMR for benefits administration since 2020. During the meeting, counsel acknowledged that the UFT Welfare Fund had an exclusive seat at the initial discussions about prescription drug data sharing under the NYC Employees PPO—well before the issue was brought to other unions.

That history changes the frame. What was described as a new, collective, and exploratory proposal was not starting from the same place for everyone. One union entered the room with an existing partnership, early access, and influence—while others were being briefed in real time.

A Call to Action — For Union Leaders and Members

Union leaders are being asked to approve a deal that hands over members’ most sensitive health data—data that will be used to sort, score, and manage care—while being told the risks are minimal.

They should reject the data-sharing agreement.

Members also need to understand the reality: you will not be able to opt out of data sharing. At most, you may be able to opt out of outreach calls or emails from UMR and their “member education” — which amounts to why you or your family member’s claims and care are denied or delayed.

You and your dependent’s prescription data will still be transferred. Your information will still be analyzed. Your care can still be shaped by systems you never agreed to.

And you will never see your score from their proprietary blackbox.

If an algorithm labels you “high risk,” will you be told? Will you know what data was used? Will you be able to challenge it—or even confirm it exists?

Or will you simply feel the consequences—more delays, more denials, more scrutiny—without ever being told why?

When the presenters were asked if members will know their individual scores fueled by their union welfare prescription data, the answer was a flat out: NO!

That is not transparency. It is control without accountability.

Members should demand that their unions say no to this deal—and insist that no AI predictive system be adopted where people are scored, categorized, and managed in the dark without direct, transparent oversight, explicit safeguards and ability to directly appeal through human review by stakeholders.

A Line That Can’t Be Uncrossed

Prescription drug data will be shared weekly with United Healthcare’s deny and delay machine—unless unions stop it.

Risk scores will be created. AI tools will shape human care.

Leverage will be carried forward into bargaining.

This not ‘business as usual’ or normal. It’s unusual.

The quiet part is no longer quiet.

The only question left is whether union leaders—and union members—act while they still can.

Learn more: